When I was a little girl, my brother and I had the most beautiful set of wooden blocks. They were a lovely honey colour, sanded impossibly smooth, and just the right size and heft for two toddlers to construct all the palaces and zoos and cities we could imagine. When we weren’t playing with them, they lived in a simple, canvas, navy blue drawstring bag, with a reinforced bottom. The blocks were all kinds of useful and fanciful shapes — there were the rectangles and squares and triangles, of course, but also animals, crescents, cylinders that became Grecian columns, and flat pieces that my brother appropriated as ramps and jumps for his toy cars and trucks. There was not a single element of branding anywhere on this, our favourite set of toys. It’s possible that a friend made them for us; I don’t remember. But someone, or a collection of someones, somewhere, made those blocks. They may have been cut by machines, but the evidence of human care and thought was there in our hands, every time we played with them.

I was mostly a bookish little girl. My mom handed me the first in a set of Ladybird Early Readers when I was nearly three. I sat down with it, started sounding the words out, and by the end of the week, I had finished the entire series of more than fifty tiny books. I lived in my own imagination, and I have been teased all my life for “disappearing into books” to the detriment of my engagement with the world around me. At the same time though, I had a deep-seeded longing to create. To make real, lasting, useful things. I didn’t want to play in a child’s toy kitchen, with plastic fruits and vegetables and branded “cans” of beans. I wanted to learn to make dinner.

One day, I somehow managed to evade both my mother and my little brother, and get a hold of not only our beautiful blocks, but also my mom’s bottle of Weld-Bond glue. Do you remember that stuff? We had a giant bottle that my mom used to repair everything. I was fascinated by it, by its potential for permanence. I had been making secret plans involving the Weld-Bond for a while. See, one of my brother’s favourite games, from when he was very small, was knocking things down. He and I, and sometimes our dad, would spend afternoons constructing imaginary structures out of our blocks; then, with great glee and much shouting, he would knock the whole thing down. Sometimes, he knocked stuff down before I was finished with building. And I had also grown old enough to realize that the mud “clay” I used to sculpt in the garden never lasted through an afternoon rain. And that no one was getting fat from the cookies I served at my tea parties. I was even dissatisfied with my tea set, because it was plastic and had cartoon characters emblazoned on it, instead of being real china, like grown-ups used.

I could see how the rectangles and squares and triangles and flat slabs of wood could be fitted together to make the classic child’s interpretation of a house — the rectangles and squares to make the base, with triangles on two sides to create the angles of the slab roof. I also finagled my pencil crayons from their hiding place. (My brother was only allowed crayons, after an unfortunate incident with his bedroom walls.) I spent what seemed to me to be a glorious afternoon, gluing my blocks together and decorating them with hand-drawn windows and doors and flower boxes. I was building. Real things. Houses that couldn’t be knocked down by a small and destructive sibling. I can still remember how it felt when the Weld bonded and the blocks didn’t come apart in my hands. I felt proud, useful, competent. It was heady. It was my first “make”.

In reality, it probably took my mom less than half an hour to discover my project. And wow, was I in trouble. I had ruined a toy that wasn’t only mine. She managed to pry apart most of the tiny houses I had so joyfully built, and she put the Weld-Bond on top of the cupboards, far out of my reach. I wasn’t allowed to touch it again, unsupervised, until I was in my teens. A few of the blocks remained stubbornly attached to each other, half houses that reproached me every time we played with the blocks afterwards. Despite the extensive vocabulary my precocious reading had afforded me, I didn’t have the words to explain to my mom what I had been trying to accomplish with my surreptitious crafting. I couldn’t convey to her the longing that I felt to make the things I saw in my head exist in the real world. She was angry, and I was sad and angry. And sore. I definitely remember being spanked.

After that, my parents did enrol me in a few creative endeavours — a kids’ pottery class, where we never got to play with the wheels in the corner of the studio and where we were directed to make monsters, which frightened me and bored me at the same time, a “creative movement” class, where my clumsiness and dreaminess left me with nothing but envy for the little girls in the ballet class next door, with their leotards and pink shoes and disciplinarian teacher, correcting their every stray from proper position at the barre. My mom taught me to knit, first with a spool painted to look like a woman, then with long and awkward metal needles that my small hands couldn’t manage well. I made long tubes of what I now know to be I-cord, then long and misshapen, holey strips of garter stitch, using violent shades of squeaky acrylic left over from one of my mom’s years-long sweater projects.

I should interject here that my mom is, and always has been a maker. She took pottery at college. She knits, she sews, and these days, she quilts. Her work is astounding. For my wedding, she made my dress from lace, the price of which made my father’s eyes water. When I went to private school, she made my uniforms to save money. I still treasure the tiny sweaters she knit for my daughters when I was pregnant with them, and they still have the baby blankets she knit, though they are both young adults, living on their own. I eat dinner off plates she made me, and drink my coffee from mugs she threw, every day. The most comforting blanket I own is one that she crocheted. It’s acrylic, and it’s known in the family as the “ugly afghan”, but it was the blanket that covered me on the couch whenever I was home sick from school. My mom can do anything that she attempts. Except cooking, but that’s a story for another day…

I learned, as I went off to school, that my reading and my thinking won me praise from the adults around me. I was “smart”. I also learned, again and again, that I was not “artistic” or “practical” like my mom. My pictures never looked, on paper, the way they did in my head. I couldn’t make my hands move right to accomplish the things I wanted them to. Of course, now I know that learning is a curve, and that no one is good at things immediately. My mom had been learning her skills from her mother from a very young age. And then she lost her mother as a teenager, and had to step in to a “womanly” role for her father and two brothers, though she was the youngest of the family. But I saw other kids, especially other girls, praised for the neatness of their work, for their ability to keep their desks tidy and their colouring and cutting in the lines. And I like praise. I like being good at things. So I steadily gave up on the things that didn’t come naturally to me, like reading had. I became dreamier. I lived in my head more and more. The longing to make never really went away, but it got tamped down as I “failed” creatively again and again. As a pre-teen, I got excited about baking. My repeated attempts at bannock resulted in a lot of ribbing about the indigestion I was inflicting on my dad. Then there was the time I mistook the salt container for the sugar, while making muffins. My mom will still bring that up. As a teen, I got yelled at a few times for attempting to creatively alter my own clothes. I learned that I was a thinker, and not a maker.

I grew up. And I was suddenly expected to be able to do practical things, like feed myself. I became a vegetarian just before university, in part because I was terrified of poisoning myself if I tried to cook meat. I decided that I wanted to be an English professor, because I couldn’t actually think of a less practical career option. Plus, I could get paid to read stuff! And I was very good at reading stuff! And writing stuff! When I moved into my first dorm room, and filled my shelves with “the classics”, my roommate looked over and asked me where I was going to keep my food. I looked at her side of the room, and wondered where she was going to put her books. She was a varsity athlete, and a kinesiology major; I survived my first year on coffee, whiskey, cigarettes, and the occasional cup of yoghurt pilfered from her side of our shared fridge. We didn’t get along.

In my second year, I joined the staff of the university newspaper, and proceeded to blow up my life and my academic career. By the end of it, I was barely attending classes, drinking far too much, and dating horrible young men. And then I got pregnant.

For all of my pregnancy with my oldest daughter, I managed to float through without thinking too much about the practicalities of raising a child. My boyfriend and I moved in together, and he had furniture and stuff. He was also a decent cook, given the constraints of our student budgets. Of course, I dropped out of university, and had no real plans beyond gestation. I was twenty. I was dumb. I planned to breastfeed, and I didn’t have to learn how to make that. It wasn’t until my daughter was nearly a year old that I realized that I would have to feed her something beyond pilfered yoghurt, heavy unleavened bread, and salty muffins. I was an adult. I was someone’s mother. And in my mind anyway, moms make things.

I did what I always do when I am terrified. I went to the bookstore.

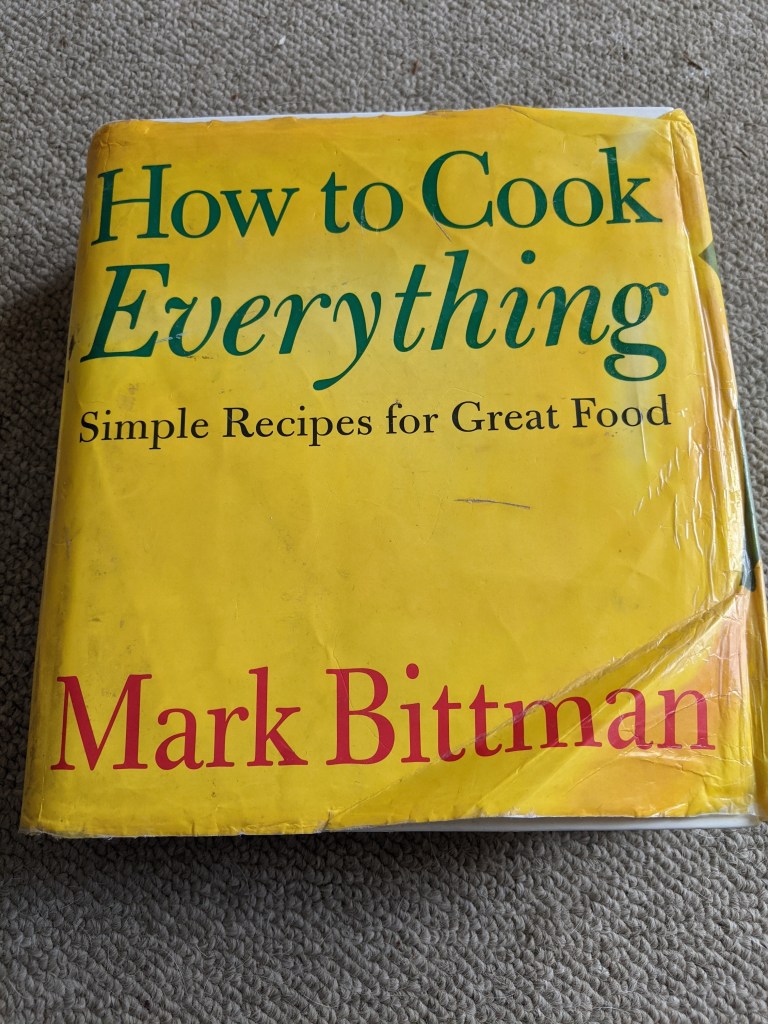

And there, I found something that would eventually change my whole life. Sitting on a display table at the front of the store, in neat and towering piles, was an enormous book with a bright yellow cover. Mark Bittman’s “How to Cook Everything”. Even the title was immensely comforting. Though we didn’t really have the thirty dollars for me to spend on a cookbook, and though I had never shown any aptitude or enthusiasm for cooking anything, I pulled out my debit card and bought the book. Then I spent hours and days reading it, when a better mom would probably have been playing with her baby. Bittman had sections telling me what equipment I actually needed to cook things. Sections on how to choose produce, and the best methods to cook different fruits and vegetables. It was the first time I had seen cooking explained as a set of methods, not a series of proscribed steps to produce a singular result. He demystified making food.

My first attempt from my new bible was a Beef Daube. I was never one to ease my way into things. It wasn’t very tasty. I was scared of salt (it could be sugar! who even knows?). But it looked stew-like, and we didn’t get sick. I started nagging my parents to buy me a food processor, so I could make bread in the Bittman manner. I was absolutely hooked.

That encounter with making, with providing food for my family, was the first time that I felt authentically adult, authentically maternal. A lot of us folks who live in their heads struggle with Imposter Syndrome; I think it’s because the things that we “do” don’t have a concrete, physical existence in the world. So really, we could be just making everything up, and tricking people that we are actually smart and worthwhile and valuable. But stew? You can’t just imagine stew. You can’t feed your baby stew that only exists in your brain. It’s real. And it doesn’t just come into existence. You have to make it. You have to cut up the meat and the vegetables, and heat the pan, and follow the steps, and cook the stuff. You have to do it.

Since my Beef Daube days, I have learned a lot about cooking. And about myself. And about making. Now, I cook every day. I bake most of our bread and cakes and cookies. I preserve food, by fermentation, by water-bath canning, by pressure-canning, by curing and smoking. I knit amazing sweaters that I wear almost every day. And socks. And hats… I make soap, and cleaning supplies, and vinegar. Last summer, I built raised garden beds. I am learning to garden, and to sew. My husband has promised me pottery classes, as a gift, when the pandemic eases.

With every skill I learn and practice, I feel more authentically myself, and more competent. I feel valuable. I feel real. I don’t believe that every person can or should make every single thing they use in their lives. We live in a capitalist culture, where time is precious and goods are commodified. But I do believe that making space for yourself to create, and especially to create useful things, is an important step to feeling at home with yourself.

This blog is called Supermarket Homestead, because I know that it’s not practical or advisable for everyone to raise/grow all their own food, make all their own clothing and so on. I don’t work outside my home, for a lot of reasons that I plan to delve into further, but I know that working for an income is an inescapable reality for the vast majority of people. So I want this space to be a place that meets you wherever you are. I want to help people learn, like I have and continue to do, to make things that have meaning and value for them, with the tools and supplies that they have access to. Too many cooking sites, too many homesteading blogs, too many crafting Instagrams seem to convey the impression that you need fancy equipment, or acreage and livestock, or the most expensive, hand-dyed yarn, to be a maker. I have a lot of thoughts about what that says about our culture, and about capitalism in general. But first I want to say that that is a lie. Making is accessible. Making is authentic, no matter how you do it. Making is empowering.

I hope that this long-winded and political introduction hasn’t scared you away. I promise that most of my posts will be about projects that I am undertaking. Tomorrow, I want to talk about blood orange marmalade. No, that’s not a metaphor. I am hoping to share at least one “bigger” think piece each week, about the meaning and practice of making, interspersed with projects and more general posts about things like the tools I use and love, and the other makers and books that inspire me. I would love to learn more about your journey as a maker too. Who did you learn from? Did you feel supported and valued as a creator? Who do you make for? And what do you love to make?

Lovely to read, dear friend! On the one hand, reading this makes me miss you more, but on the other hand, I feel like we are visiting!

LikeLike

I miss you so much! And one of the things I want to write about is how making brought us together. All those days working in our kitchens together ❤️

LikeLike

I’m so delighted that you’ve launched your blog. Your first blog entry is so warm and inviting and utterly captivating, and I can’t wait for more from you. I wish we could have a proper visit, but this really is the next best thing. More, please!

LikeLike

Thank you, Regina ❤️ One day, I am getting to Rhinebeck!

LikeLike

Love you, Sophie. I look forward to reading more. You are amazing and mostly I will just read along and I’m sure sometimes I’ll be inspired to try.

LikeLike

Thank you so much, Jocelyn! I hope I share some projects that inspire you ❤️ You and your daughter are pretty amazing makers too!

LikeLike

Reading this evoked all sorts of feelings, both the experiences I have had in my childhood and as an adult. I also have a crafty mum that taught me a lot of stuff, most importantly knitting, but I also learned quite a bit from being part of 4H as I was growing up. Like you, I get extreme satisfaction from being able to look at and use things I have made with my own hands. I like to learn and try new things, and that is one of the reasons I will look forward to read your blog. You are very inspiring, and I wish you all the best of luck with this new “home”. I will love to come visiting!

LikeLike

Thank you, Elin ❤️

LikeLike

What a wonderful start to your blog Sophie. Your words so beautifully capture you, and your passion for making. Thank you for sharing and I can’t wait to read more.

LikeLike

Thanks for the encouragement ❤️

LikeLike

I love you, Sophie. Absolutely looking forward to everything coming next.

LikeLike

Love you to Ridgely ❤️ Thanks for reading!

LikeLike

Oh Sophie, I am beyond excited to learn about you and your making in this format. I am so grateful for you my friend and this is a beautiful testament to that big beautiful brain and heart of yours.

Much love to you

LikeLike

I loved reading this and look forward to hearing more about your story and what you have to share. I think we all experience feelings of imposter syndrome at times and that’s natural. I have too considered starting a blog but what would i even share?! I really liked where you said I want to meet you where you are. I think that resonates with me most.

LikeLike